Texts

The Aesthetic Hyper-Object in Experimental Short Film Practices: Lina Sieckmann and Miriam Gossing’s Art Documentaries

Dorothee Ostmeier

University of Oregon

Abstract

Short experimental films by the German female director duo Lina Sieckmann und Miriam Gossing put domestic environments on cinematic display in new and challenging ways. The essay discusses the links between the films’ documentary agendas, surreal visual montages, and poetic feminine voice-overs. Selected films are placed into dialogues with Michael Renov’s concept of aesthetics in documentary film and Timothy Morton’s notion of the “hyperobject.” This theoretical framework highlights the tensions between the films’ powerful aesthetics and feminine queer desire as they decenter socially ingrained dualisms.

Biography

Dorothee Ostmeier is Professor of German, Folklore and Public Culture and Head of Theater Arts at the University of Oregon. She is the author of monographs on postwar Jewish language philosophy in dramas of Nelly Sachs, and on Gender/Sex Debates in the early 20th century. She also edited the volumes “Brecht, Marxism, Ethics” for The Brecht Yearbook (2010) and Poetic Materialities: Semiotics of Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s “Wanderer’s Nachtlied” and “Ein Gleiches.” COLLATERAL – Online Journal for Cross-Cultural Close Reading, Fall 2017.Her current research project Portals and Shapeshifters in Gothic Fantasies to Postmodern Digital Culture” focuses on fantasy’s stakes in crossing the borders between reality, fiction, and virtuality.

OSTMEIER, Dorothee. The Aesthetic Hyper-Object in Experimental Short Film Practices: Lina Sieckmann and Miriam Gossing’s Art Documentaries. Konturen, [S.l.], v. 12, p. 47-72, apr. 2022. ISSN 1947-3796.

——-> Full Text as PDF

MÉLANIE VAN DER HOORN,

in „SPOTS IN SHOTS – NARRATING THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT IN SHORT FILMS“

______________________________________________

Patrick Gamble,

„Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be“ (Souvenir),

Kinoscope, 25fps Festival Zagreb

(…) „Another film that revived the past through the stimulation of unconscious memory was Miriam Gossing and Lina Sieckmann’s “Souvenir” (2019). Set aboard an abandoned cruise liner during a dark and stormy night, the ship’s eerily empty corridors and dance halls are brought to life by the testimonies of various women who lost their husbands to the sea. Exploring the totemic power of romantic ornaments, the film positions these interviews against the souvenirs their husbands brought home. Each keepsake radiates with memories of abandonment and loss, but Gossing and Sieckmann are more interested in negotiating the conflict that arises when material objects from places of tourism are implanted in the home.

The best example of this is a pair of earthenware Staffordshire dog figurines. Sometimes referred to as “Wally dugs,” these porcelain statues often took pride of place on the mantelpiece. However, after discovering they were routinely purchased in the brothels frequented by British sailors, their role changed, with one woman explaining how she would use them to signal her lover. Moving the dogs to the windowsill, she would place them back to back if her husband was at home, but if the dogs were facing each other, it meant the coast was clear.

These items of memorabilia, coupled with the faded décor of the cruise liner, allude to a history of seafaring in which luxury and exploitation go hand in hand. Interrogating the fetishization of intangible experiences, “Souvenir” depicts how the legacy of colonialism lives on through the trinkets lining the mantlepieces of many UK homes. But this nostalgia isn’t just confined to Britain, with many of Europe’s former imperial powers struggling to reconcile their postcolonial melancholia.“ (…)

25fps Festival 2019,Patrick Gamble | Nov 15, 2019 | Kinoscope

////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Phillip Fernandes do Brito,

„The Unknown Lover“ (Desert Miracles),

Catalogue New Talents Biennale 2016

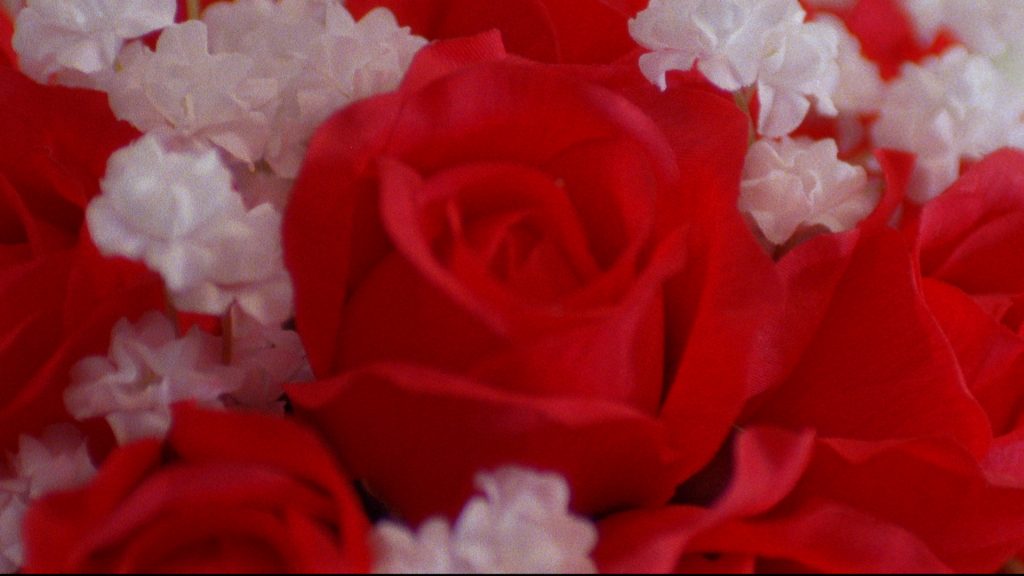

We are immersed in an intimate mood while watching the curvilear forms fade into each other like the subdued vibration of an abstract painting, which the fine granulation of the 16mm film empowers. The pastel colors of the forms build up from white via rosé and fuchsia to a saturated red when a female voice suddenly begins a monologue. From offstage, she addresses her letter to an anonymous partner with the phrase “My dear lover”. The intimate softness of her voice floats above the wedding bouquets of silk flowers, which in their artificiality emerge as rentable props in American wedding chapels, when suddenly the double-doors open onto a hall. The constant fresh colors of the lifeless flowers—whose bouquets were held by countless women and enriched by just as many expectations—take their place in a staged scenario of ever alternating architectural designs: a serial pattern whose tableaus the camera portrays within a fixed framework so as to capture the aura of the axial-composed interiors with seating accommodation. You find everything here: from pink foliage, pompous halls, up to the neon-lit diners or slot machines from the 50s.

Though the chapels thus resemble their location in the desert state of Nevada as composites from different styles and periods, they are nonetheless empty of people. They remain quietly awaiting their deployment by those for whom they have been designed. Like the optically centered corridors, the young woman’s hesitating voice fills the uninhabited rooms, describing her fears, expectations and dreams, a recitation that seems to lead her ever deeper into imagining the fulfilled life she longs for. Her expressed desire is actually a collective one, since her fictional monologue—not initially revealed to the viewer—is based on anonymous blogs pieced together from Internet wedding forums. Nothing stands above the accumulated wish to be completely and truly loved.

Similar to the presumably pure and “genuine” wish that with the question “Will you marry me?” seeks to find its fulfillment, the chapels’ artificial scenarios culminate in an emblematic wish fulfillment. Its symbolic reflection is manifest in an alluringly illuminated Tiffany window, whose central image consists of a surreally perfect rose. With this hypnotic effect, it draws the viewer into the ritually economized staffage of the rooms’ stagings, whose originally religious symbols have been replaced by an iconography of the amplified value society places on love. References in the text likewise enlarge on the recurring Hollywood narrative of romantic couples, whose wishful fancy is presented within certain scenarios and thus participates in the pictorial production of this collective idea.

In this respect Desert Miracles zeroes in on its own analytical vocabulary that does not fix its gaze on love’s décor, but squarely on love itself. With their histrionic staging, the suggestive power of the settings unmasks itself in static takes in such a way that gives the last take a hyper- or unreal look via its refractive reverse-angle, all of which offers a view onto the dream city, Las Vegas, above the approaching Cadillac of the King.

Philipp Fernandes do Brito

__________________________